1. A city shaped by empires, not erased by them

Serbia traces its roots to early Slavic settlements, rising under the medieval Nemanjić dynasty and briefly becoming a Balkan power in the 14th century before centuries of Ottoman rule. Belgrade sits at the center of this story. One of Europe’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, it has passed between Byzantine, Hungarian, and Ottoman hands, and today feels less curated than accumulated. Its layers are visible, sometimes messy, and very much alive.

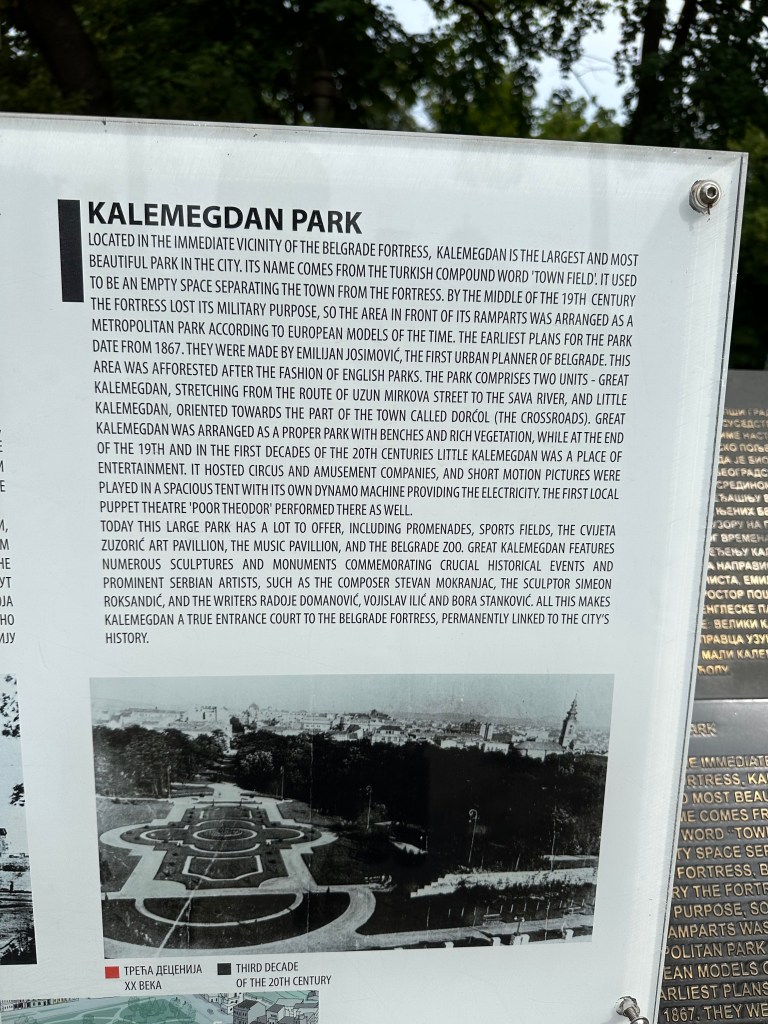

2. Kalemegdan is where Belgrade makes sense

Belgrade Fortress, or Kalemegdan, crowns the confluence of the Danube and Sava and forms the historic core of the city. Built, destroyed, and rebuilt by successive empires, it reflects Belgrade’s role as a strategic crossroads rather than a ceremonial capital. While the fortress includes landmarks like the Victor Monument, Ružica Church, St. Petka’s Chapel, and the Military Museum, the real payoff is quieter. Standing by the gates, watching the rivers merge below, you feel why this spot has mattered for centuries.

3. The city’s pulse lives in its streets

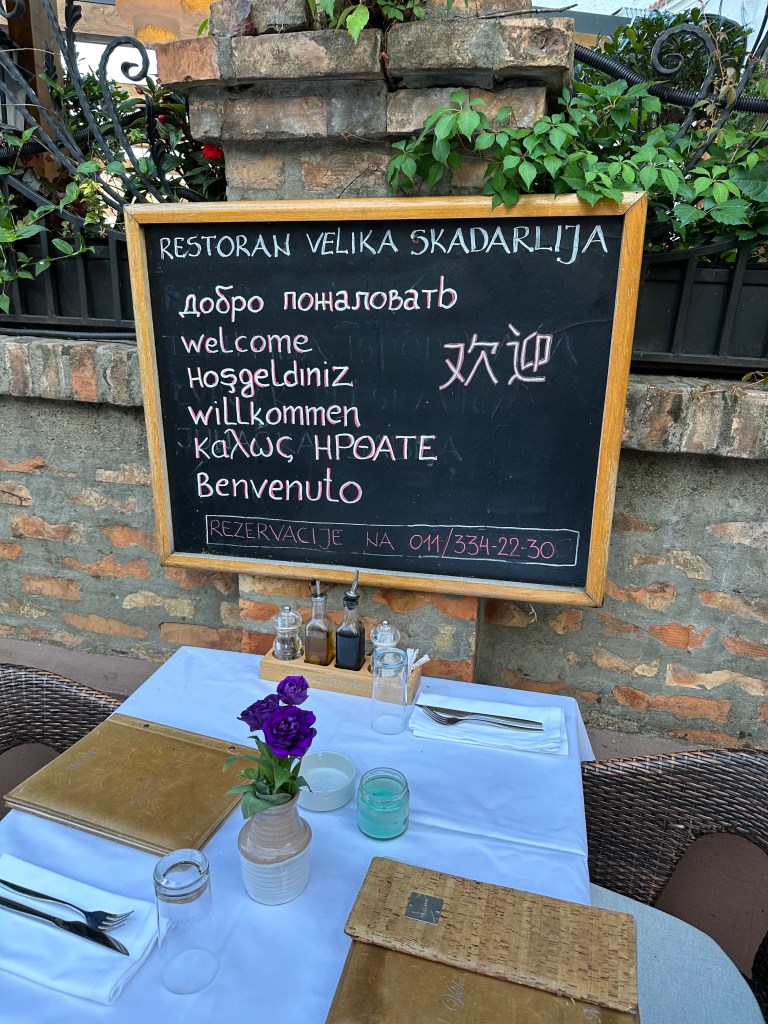

Belgrade’s energy reveals itself on foot. Knez Mihailova is the main artery, lined with cafés, galleries, and shops, linking Republic Square to Kalemegdan. A few minutes away, Skadarlija shifts the tone entirely. Short, winding, and preserved as a cultural-historical area, it comes alive after dusk with musicians and packed restaurants. It feels less staged than remembered, which is part of its charm.

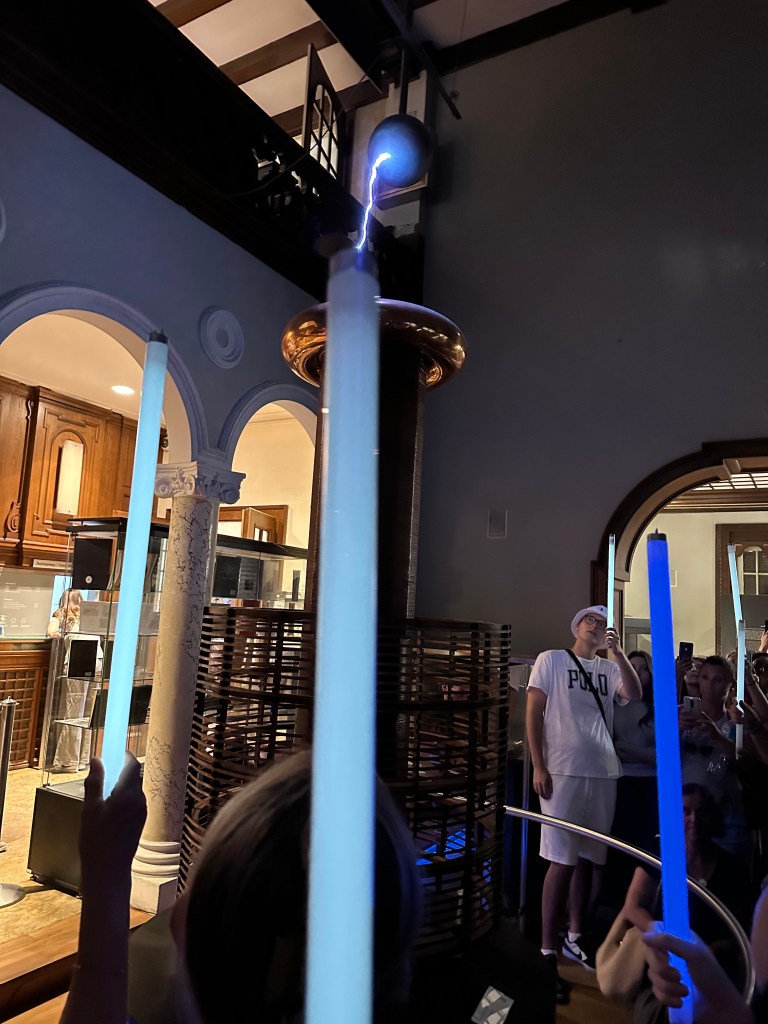

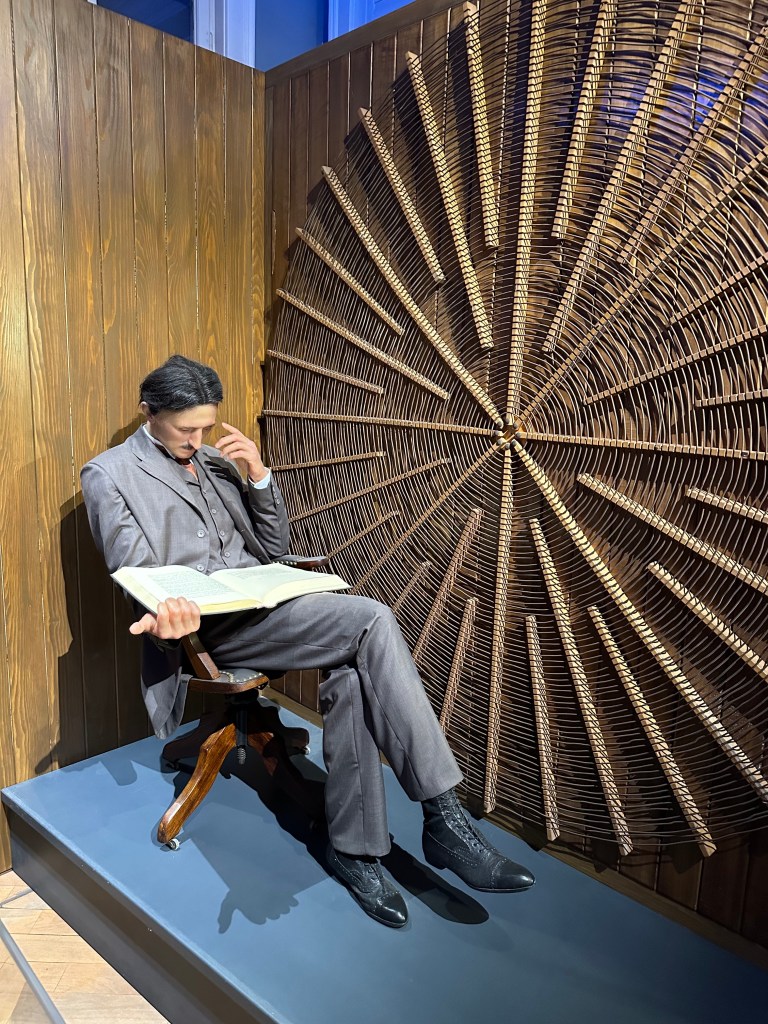

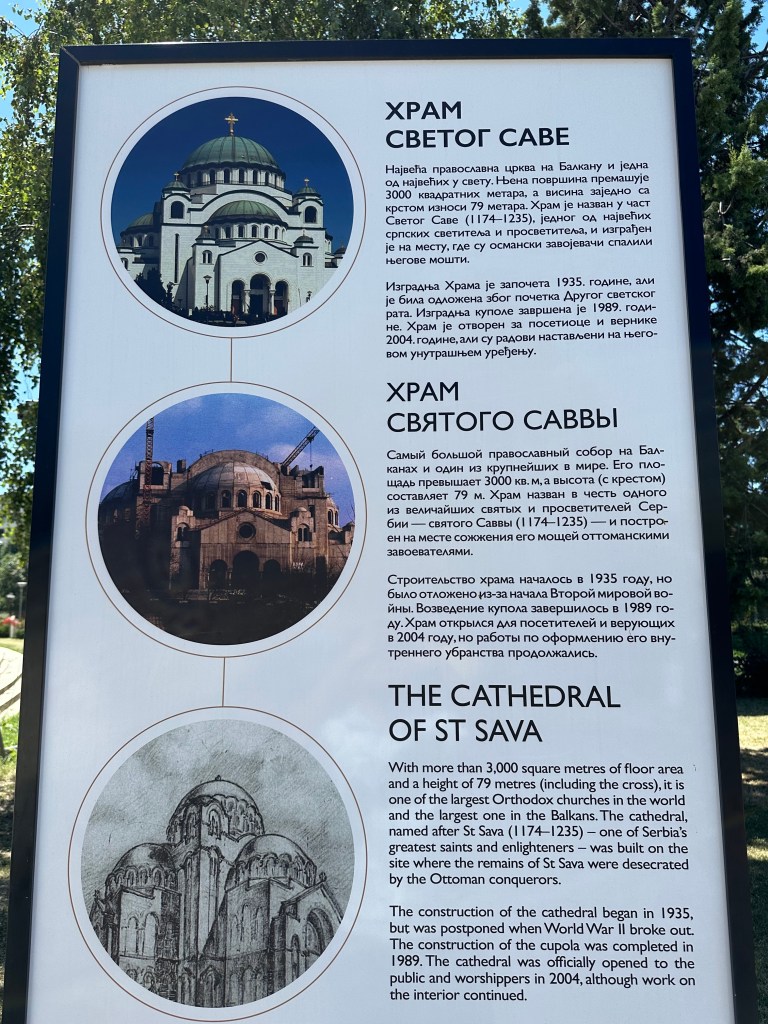

4. Belgrade’s Icons: Mind and Spirit

The Nikola Tesla Museum is a compact but meaningful tribute to one of Serbia’s most celebrated figures. The staff are warm and enthusiastic, and the Tesla coil demonstration, with visible electrical charges cracking through the air, is a genuine crowd-pleaser. Nearby, the lesser-visited National Museum of Serbia offers an under-the-radar but solid introduction to the country’s history and cultural arc. If Tesla speaks to Serbia’s scientific legacy, the Church of Saint Sava is about scale and symbolism. Dominating the skyline with white marble, granite, and one of the largest Orthodox domes in the world, it feels ancient in form despite being modern in construction. Inside, vast golden mosaics shimmer across the interior, creating a space that is monumental rather than ornate. Built on the site where Saint Sava’s relics were burned, the church reads as a quiet but unmistakable assertion of identity.

5. Food here is direct, comforting, and unapologetic

Serbian cuisine leans heavily on grilled meats and pies. Ćevapi are the flag bearer, even if Bosnia claims them too, and they rarely disappoint. Ajvar, made from red peppers, eggplant, and garlic, was the standout for me. Sweet, smoky, and just spicy enough, it works with almost everything. Serbian salad, a simple mix of tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, and salty white cheese, shows up everywhere and does exactly what it needs to do. Burek is a staple and Trpković Bakery lives up to its reputation with crisp, generously filled pastries, though slightly greasier than ideal. Meals are often paired with rakija, the local fruit brandy that is deceptively strong, sometimes spicy, occasionally anise-forward, and very much not meant to be rushed. Desserts are less emphasized, but the famous Moscow Cake at Hotel Moskva is spoken of with reverence. Visually stunning, though for me, overly sweet and flatter in flavor than expected.