1. History and identity

Romania’s history is one of repeated absorption and re-formation. The land that is now Romania was first inhabited by the Dacians and later folded into the Roman Empire. Over the centuries, the region saw successive waves of control by the Cumans, the Ottomans, and later the Habsburgs, even as a Romanian identity began to take shape under figures like Michael the Brave. Medieval principalities such as Wallachia and Moldavia eventually consolidated into a modern Romanian state in the late nineteenth century. After World War II, Romania became a socialist republic under Soviet influence. When that system collapsed, it re-emerged once again as a modern republic. That sense of continuity under repeated disruption is central to understanding the country.

2. The city itself

Bucharest was better than I expected. It feels dense and sprawling at the same time. Parts of the city reminded me of Mexico City, perhaps because of Herăstrău Park, a vast green space in the center that plays a role similar to Chapultepec. The wide boulevards reflect Soviet-era urban planning, and the brutalist buildings reinforce that impression. Bucharest has been the capital since the formation of the Romanian state, and its coat of arms is derived from that of Wallachia, another reminder of how deeply history is embedded in the city.

3. The Palace of Parliament

Also known as the People’s House, the Palace of Parliament is excess made physical. What it lacks in taste, it attempts to compensate for with scale. It is the largest civil administrative building in the world and also the heaviest. Built between 1984 and 1997 during the communist era, it houses the Parliament, the Constitutional Court, and several museums. Despite this, it is estimated that nearly seventy percent of the building remains unused. Tours are offered daily and tend to sell out during the summer, which says something about our fascination with monuments to ambition.

4. Music and architecture

The Romanian Athenaeum, or Ateneul Român, was built in 1888 by the Romanian Athenaeum Cultural Society and remains one of the city’s architectural highlights. The neoclassical exterior is regal without feeling overwhelming, and the ornate domed roof stands out immediately. Inside, the entry halls and staircases create a sense of ceremony before opening into the main concert hall. It feels like a building designed not only for music, but for occasion.

5. Old Town and living history

Bucharest’s Old Town is relatively compact and dominated by heritage buildings owned by government bodies and local institutions. The Stavropoleos Monastery feels like an anachronism. Built in 1724 by the Greek monk Ioannikios Stratonikeas, it began as a monastery supported by an inn, which was common at the time. Earthquakes and nineteenth-century demolitions destroyed most of the complex, but the church endured. Today it is complemented by a twentieth-century building housing rare icons, fresco fragments, and a small library. Nearby, Cărturești’s Old Town location stands out for its bright, open interiors and layered floors. It is an easy place to linger and a good stop for thoughtful local souvenirs.

6. A day in Transylvania

Exploring Transylvania was one of the things I was most looking forward to, but travel delays forced me to cut Brașov from my itinerary. I still managed a day trip. Romania’s train system feels like a holdover from the Soviet era. It is not glamorous, but it is functional and reliable. Sinaia, the gateway town, has the feel of a hill station, with cooler weather and greenery that offered relief when Bucharest was reaching forty-four degrees Celsius. I skipped Bran Castle, often marketed as Dracula’s Castle, because of its Disney-like reputation and the weak historical link to the legend. Peleș Castle, on the other hand, was worth the effort. Once the summer retreat of King Carol I, it is opulent without feeling kitsch. Technically a palace, it blends Neo-Renaissance and Gothic Revival styles reminiscent of Neuschwanstein, with Saxon and Baroque influences throughout. Its one hundred and seventy richly decorated rooms showcase themed interiors and an extraordinary collection of art, arms, and decorative treasures.

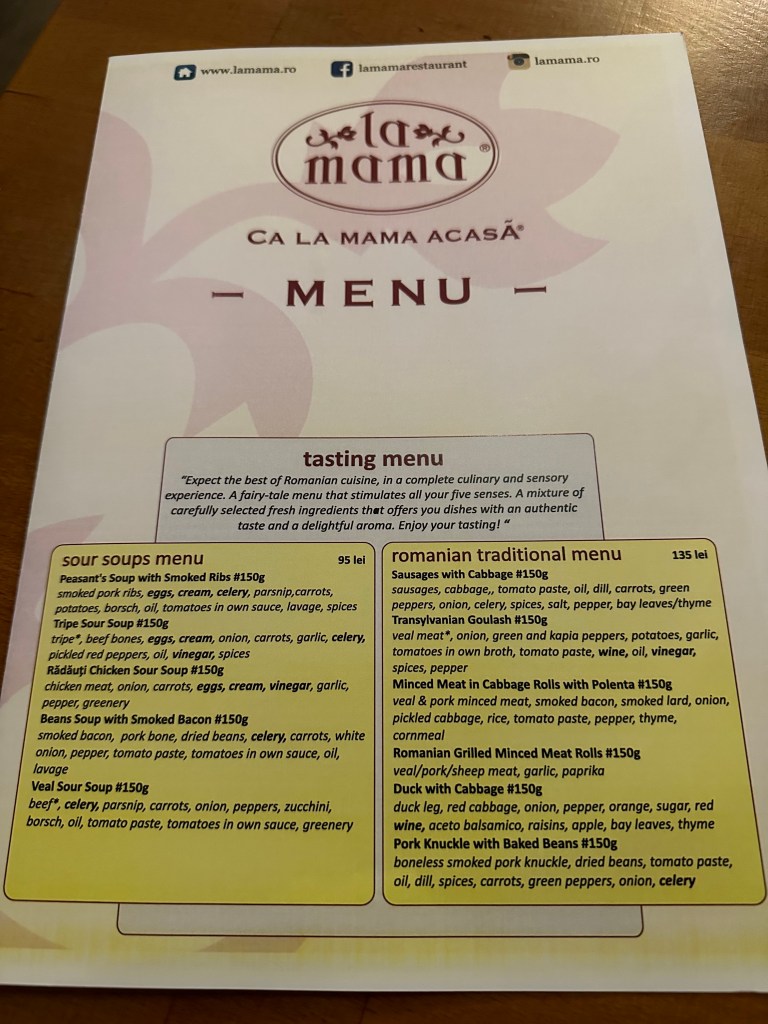

7. Food and small surprises

Romanian cuisine is unapologetically meat-forward, shaped by agrarian roots and cross-cultural influences, particularly from Greece. Many classic dishes are rich and filling, often paired with polenta. Caru’ cu Bere, a historic beer hall in Bucharest’s Old Town, is more about atmosphere and beer than exceptional food, but the setting alone makes it worth a visit. In Transylvania, the cuisine shifts closer to Hungarian flavors, with dishes such as langoși and colaci. A completely non-traditional highlight was French Revolution, a patisserie in Bucharest. The éclairs, especially the pistachio, were exceptional and could easily hold their own against the best in Paris.