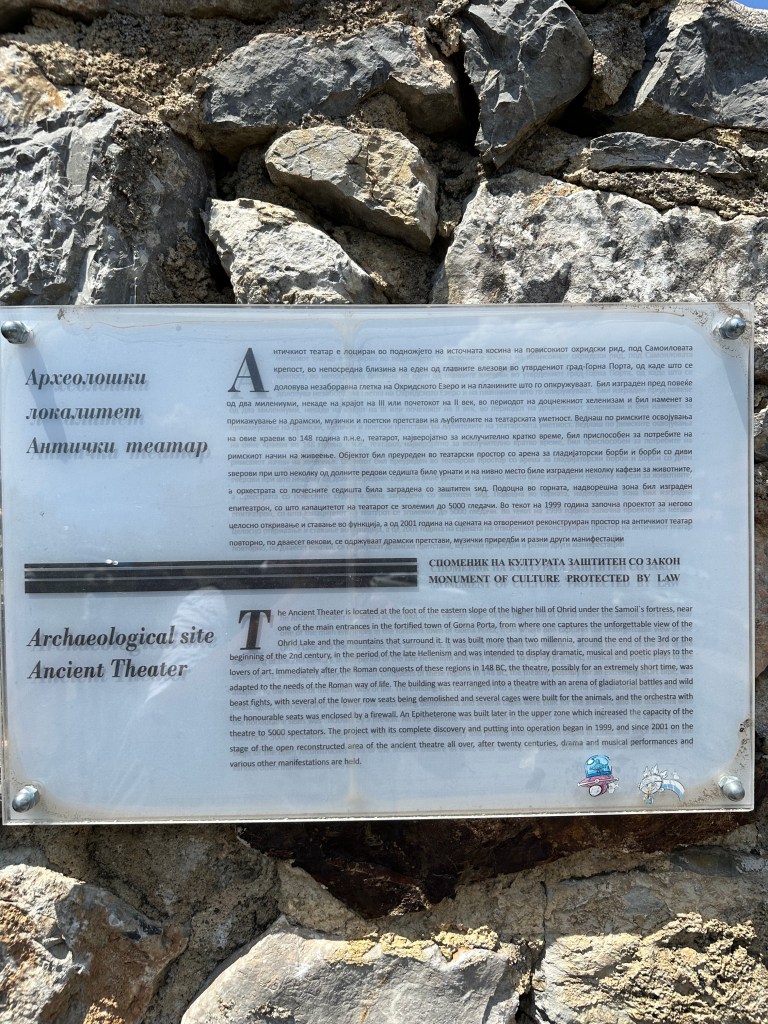

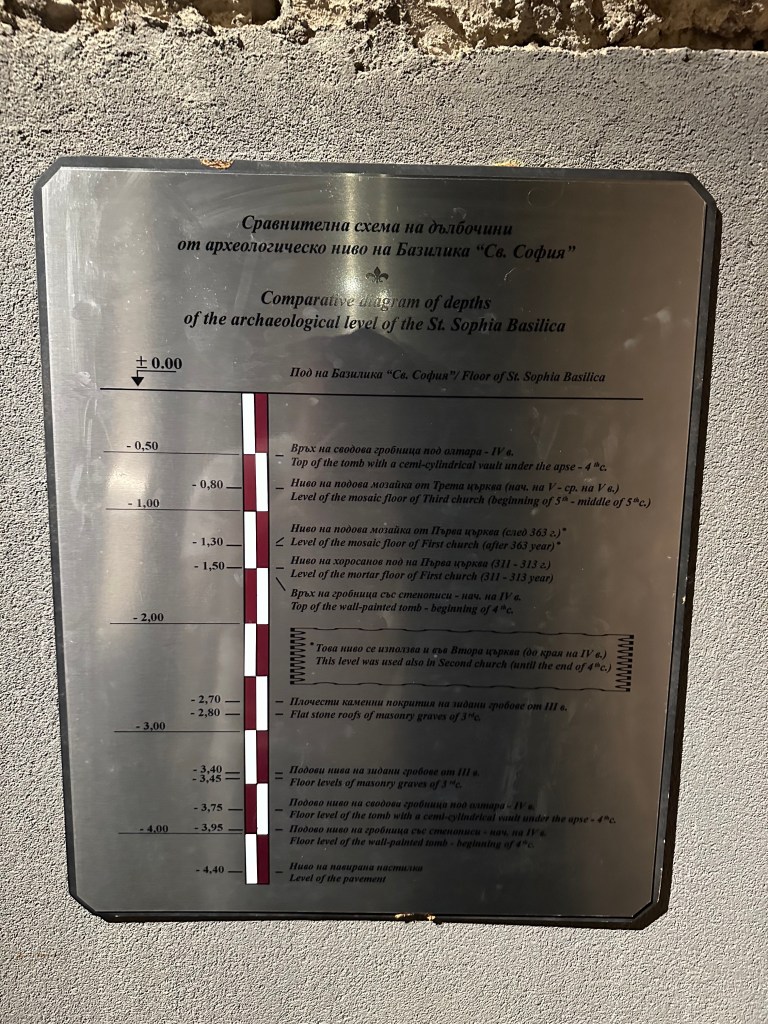

1. A city built in layers, not chapters

Sofia’s history does not move neatly forward. It stacks. As Serdica, it flourished under Roman rule and became an early Christian center where basilicas were woven directly into everyday urban life. In the medieval period, under Byzantine and Bulgarian rule, the city evolved into a fortified religious and commercial hub and eventually took the name Sofia, after the Church of Saint Sofia. Nearly five centuries under Ottoman rule then turned it into a multi-faith administrative capital, layering mosques, markets, and Orthodox churches onto ancient foundations. What you see today is not a single era. It is all of them at once.

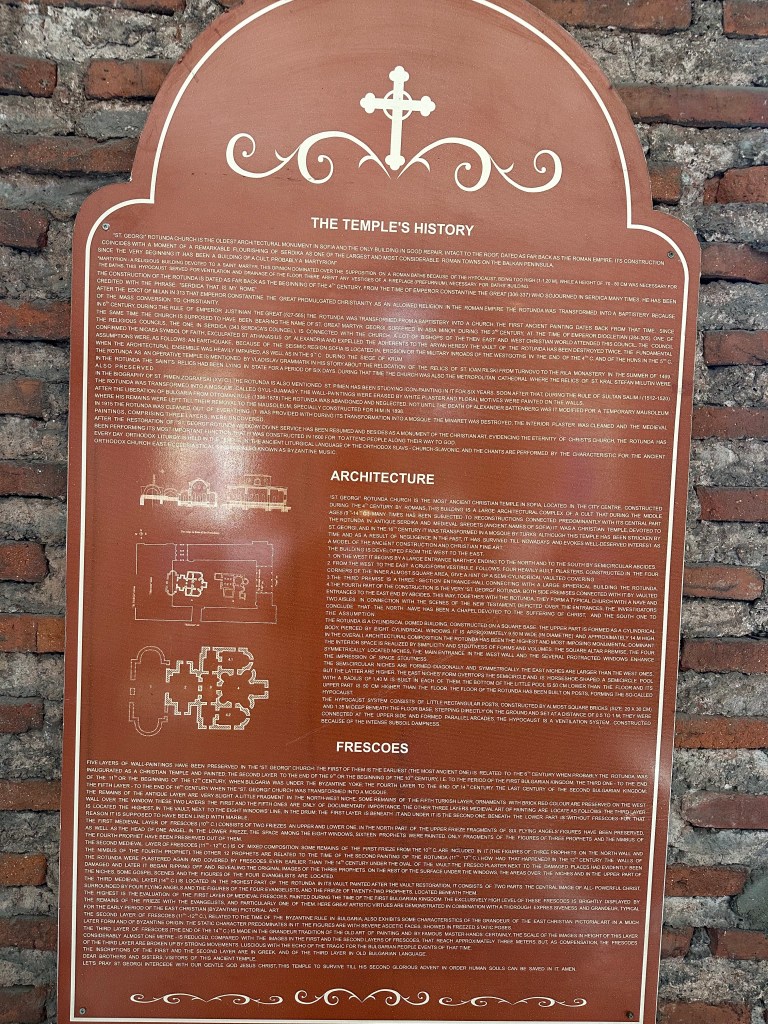

2. Why there is a church on every corner

Sofia’s dense church landscape exists because nothing was ever fully erased. Christianity took root early in Roman Serdica. Bulgaria later aligned with Byzantium, not Rome, in 864 CE, firmly placing the city in the Eastern Orthodox world. During almost 500 years of Ottoman rule, the religion survived quietly through small, low-profile churches that were tolerated but never celebrated. After independence in 1878, churches became symbols of national revival, adding monumental landmarks alongside much older sacred sites. It does not feel redundant. It feels layered. Ancient foundations, underground survival, and modern nationhood all share the same streets.

3. An Orthodox skyline that feels both ancient and Russian

From the austere Saint Sofia Church, the city’s 6th-century spiritual core built over Roman ruins, to the breathtaking scale and gilded domes of Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, and the compact, onion-domed Russian Church of St. Nicholas, Sofia’s churches tell a story of liberation-era ties to Russia layered onto much older Byzantine and Bulgarian roots. This is why the skyline feels unmistakably Orthodox and, at times, distinctly Russian without ever losing its age or gravity

4. European charm, with Soviet scars still visible

Downtown Sofia feels classically European, anchored by landmarks like the Ivan Vazov National Theatre, a symbol of early-20th-century cultural confidence. A short walk away, the Sofia History Museum, housed in a former Ottoman bath later reused during the socialist era, traces the city’s journey from Roman Serdica to communism. Yet Sofia’s time in the Soviet sphere is impossible to miss. Monumental blocks, wide boulevards, and buildings where communist insignia have been deliberately scraped away still carry the outlines of a very recent past.

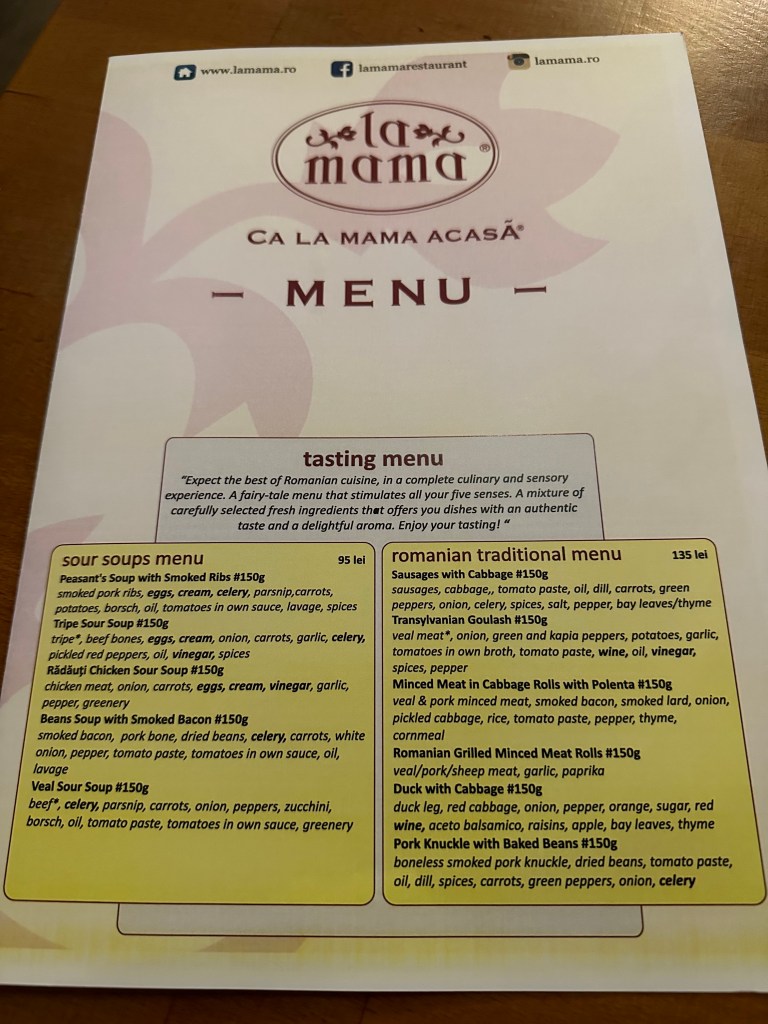

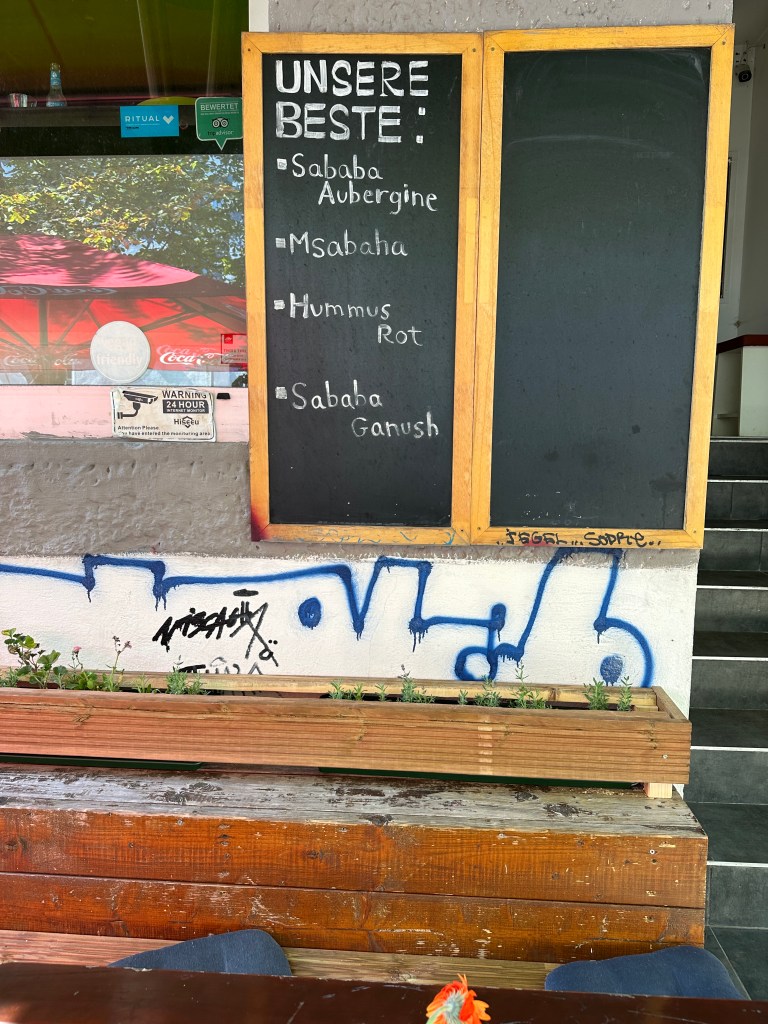

5. A cuisine rooted in fields, not finesse

Bulgarian food reflects its agrarian roots. Simple, seasonal, and Balkan at heart, with clear Greek influence. Shopska salad, often called the national dish, combines tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, and sirene cheese. Though found across the Balkans, it was formalized in the 1950s by the state tourism agency Balkantourist. Banitsa, a filo pie cousin of burek, stood out for its exceptionally delicate, flaky layers and warm, fresh cheese, noticeably better executed than versions further north. It is often paired with boza, a thick, mildly fermented grain drink. Mekitsa, casually referred to as a donut, is closer to fried bread, somewhere between a poori and a beignet, served with jam or sugar and cinnamon and eaten exactly when it is still hot.